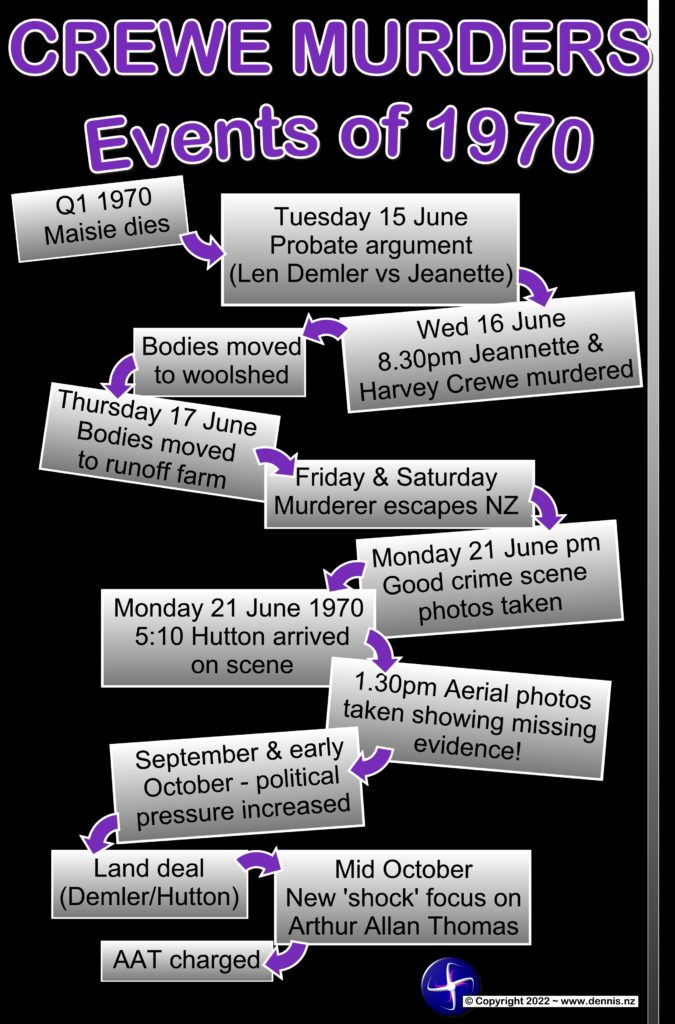

A recent new friend heard that I had written a few books and he asked me a truckload of questions about the Crewe Murders. Not always connecting with those under my age, I asked him how old he was. Over 70 means that he was around when they happened. It was a pleasure talking to someone who knew the significance of these murders. Here’s a few commentators’ comments, Pat Booth, Alice de Sturler and Ross Meurant, along with my comments. Enjoy

Lessons from the Murder-Suicide Theory

Pat Booth was the first ‘bulldog’ investigator and did enormous work in regards to exposing the Police corruption surrounding the dodgy false arrest of Arthur Allan Thomas. Called by his colleagues as “the journalist’s journalist” and to my mind the journalist of the age, Pat’s persistence in holding onto a theory well after evidence shows otherwise has huge lessons for us.

Like the Police originally believed when they found that both bodies were missing, Pat believed that the Crewe’s murder was a murder-suicide, and he did so until his dying days despite evidence to the contrary.

It wasn’t a murder-suicide. Harvey was killed outside by the East gate and his wife Jeannette shortly following in an execution-style murder inside as she was held down and repressed. Harvey’s body was dragged inside and put on the lounge seat where he bled while the perpetrators planned their next move – taking the two bodies to the Crewe’s woolshed, then to their runoff farm up by the Waikato River.

This dogmatism causes failure in logic and a major lack of understanding. Sadly people who hold onto cherished beliefs often demonstrate their ignorance. It is a lesson for truthseekers to remain flexible in our minds but to be cautious about new learning – we must seek evidence, basing our assessments on fact.

Alice de Sturler

On July, 2011 Alice said:

In the magazine “North & South,” Chris Birt makes a strong case for an in-depth review of Len and Norma Thomas Demler’s involvement in the case. Note that Norma is not related to Arthur Allan Thomas.

Strong ties have existed between the Demler and Thomas family for some time. The siblings in the family married each other. Len’s sister Noelene married Norma’s brother Brian in 1952. In 1972, after being widowed, Len married Norma.

It is a logical fallacy to think that just because one of the Thomases was set-up (Arthur was) that the other siblings are or were innocent of all dishonesty. They aren’t and weren’t as evidenced from recent events where family has attempted to obtain ‘a slice of the action’, and past events where John Ingley reported deception afoot.

Likewise it is foolish to take the word of a proven liar (Bruce Hutton comes to mind), or to trust those with a vested interest (how many does THAT include), or to assume that just because one cop is found to be crooked they all are (or visa versa).

In “North & South” from July 2010, Birt describes the case through Vivien Harrison’s eyes. Vivien, the ex-wife of Arthur Allen Thomas, passed away in 2011. Vivien starts with her own life, her family and how she ended up in New Zealand. She describes the life on the farm and the dreams she shared with Arthur. Despite tight finances, the couple managed and had long-term goals. They were on their way of realizing them when disaster struck twice. The Crewe Murders upset the entire part of the country and dominated life. On top of that, Arthur, a man she knew was at home with her, got arrested for their murders.

Birt describes the Crewe family and zooms in on Jeannette’s family. Jeannette’s mother Maisie disinherited her daughter after Heather married a divorced man. After Maisie’s death, it turned out that she had left her share in the family farm to her daughter Jeannette instead of to her husband, Len. Len in turn, disinherited Jeannette. The picture that emerges is a family torn apart by money and of people not able to see beyond perceived notions of status. These dynamics should be kept in mind when reviewing the case. After Maisie’s death, Len remarried to Norma. Curiously, it seemed he lived separate from her until he sold the farm and only then joined her in the house where she still lives.

The story in the magazines shows you the hate mail Vivien received. It also shows how she almost got dragged into the case if one witness had not been steadfast in denying it was Vivien he saw in the Crewes’ yard. Remember that baby Rochelle was found alive and unharmed. Hungry and dirty but, alive. In the house, dirty diapers were found piled up on a refrigerator. This is an indicator that someone had been in the house to care however summarily for Rochelle. The baby was probable fed but maybe not regularly. Who did that?

John Ingley names her – Pamela-Anne who ‘played identity games’ with her look-alike relative Leslee Sinton in his book I Fed the Baby. The other thing to note is that Rochelle Crewe was not, “in her cot” the whole time from the Wednesday night through to Monday. Deceivers even to this day still love to distract. Remember that Friday and Saturday she was seen out and about, people trying to pretend to the world that things were normal?

Birt shows in his articles the many mistakes made and zooms in on the man who would not change his testimony. Bruce Roddick stated that the woman that he saw was not Vivien. He knew Vivien. He went to the police and then for him, the nightmare started. His testimony did not fit the theory that police was piecing together. Despite subtle and not so very subtle threats, this man stood by his statement and probably saved Vivien from the hell that Arthur was subjected to for many years.

The Crewe murders could have been solved. Police chose to select their suspect instead of really investigating the case. We cannot say with certainty why. The fact that they messed up is clear and undeniable.

Alice assumes here, in error that “Police” were a coherent team who did not know who did what

Former NZ police officer Ross Meurant was assigned to the Crewe case as crime scene detective. He stated that in those early days, Len Demler was on the radar as a suspect.

And for very good reason too! While it was widely suspected that Len Demler was guilty of the crimes, what is not widely known and what is even today not properly understood is that he had autism. He was also known to Bruce Hutton and drank with the cops at the Mangere Pub in Bader Drive. This knowledge is why Andy Lovelock and his boys removed the photos of the tavern from the Mangere Historical Society as one of the first things they did when they commenced their review in 2010. Police covering for their own again – surely not? The number of photos taken and whether or not they were ever documented and will ever be returned [they will never be] is just a minor blip on the proverbial sea of iniquity! It would not be healthy for the Police reputation if it ever be found that photos of Len Demler drinking with Bruce Hutton now would it?

Norma, then Demler’s partner, was the woman Bruce Roddick saw in the Crewes’ yard. Being Demler’s partner, it would follow that she had helped him care however summarily for Rochelle.

Alice doesn’t know how close to the bone she has got here because it is clear to me that Rochelle was actually cared for by the Demler family outside of the murder house for the first few days and only returned to the murder house when certain things had progressed sufficiently that the balloon could go up! I can tell you most emphatically that the Police photos of Monday 22 June 1970 do NOT show a cot that contained a two year old for 5 days!

As anyone who has been to the Crewe farms will know, Len Demler’s house, path between Len’s house and the Crewe house and the Crewe woolshed where the bodies were taken on the Wednesday night are not clearly visible from the road.

However, nothing points to her being a murderer and I do not believe she is responsible for the Crewe Murders. But she did know something and till this day, she is not talking. Len Demler knew much more than he told police. Whether he pulled the trigger on both Harvey and Jeannette, we will never know.

No, Alice. We do. Many of us do. He didn’t.

Read how everyone who contradicted the police got the nightmare treatment. Not just Roddick experienced this but also Graeme Hewson, Harvey’s best friend.

This cover-up has continued and continues to this day, more than 50 years. I have shared previously of how the corruption has spread through many industries – the judiciary, the legal, the Police, the media, politics. Even to this day it is too hot a subject to deal with openly and honestly. A political hot potato now.

After hearing about his best friend’s fate, he drove out to help police in any way he could. In 1970, he helped search the farm for evidence in the garden around the Crewes’ house. He went through dirt. He searched in and around flowerbeds near the back gate. He found nothing. However, in 1972, he browsed through a booklet by the New Zealand Herald about the Crewe Murders. In that booklet was a photograph of Detective Charles pointing to the spot where they found the cartridge that incriminated Arthur Allen Thomas. Hewson knew that if a cartridge had been in that flowerbed he would have found it. He had been that thorough and determined to help police find the killer of his best mate and his wife. So, he contacted Thomas’ lawyer. And that phone call unleashed the nightmare the Hewson family had to endure for the next decade.

It is always hard to believe that police can be corrupt. How could that be possible? Ross Meurant wrote an article about police culture and it is worth reading. After that, it will become clear to you how this case was doomed from the start and why we will never have a conviction in the case of the Crewe Murders

Deep in the forest: Ross Meurant

David White/Sunday Star-Times | Saturday, 27 October 2007

CHANGED MAN: Ross Meurant believes police culture is introverted, self protecting and lacking objectivity.

Ross Meurant explains in his own words on how he has changed, how police culture has not, and why we should hold off on new anti-terror legislation.

Like most recruits, I entered the police as an impressionable young man with a basic education, from a working class environment in provincial NZ. There were hundreds of peers like me, before me and after me. I was nothing special but I was altruistic. We were all cannon fodder. Easy to manipulate. We looked at the forest before us in awe.

The moment you step into the police, this subculture within NZ culture hits you. You are immediately part of the thin blue line. You are part of a team and that team looks after itself. You are special. You are the border between good and evil. The attitudes of the police instructors, armed not with teaching certificates but with ten years’ exposure to the police subculture, either consciously or subconsciously invite you into the forest.

I find Ross’ description here so important, not so much because he was involved in the Crewe garden search on his first homicide investigation (although he was), nor because he stood up to his leaders’ encouragement to BS in court (which he did) but because his description here of the forest explains the situation relating to corruption so perfectly.

Nobody is a saint – nobody – and this forest can be described in a hundred ways for a hundred different situations, but Ross’ explanation here explains the pressure of peers, of systemic corruption that sets good people up to fail morally. It’s the thinking that the system defends itself. It must do for it to survive. Small may be beautiful, but power protects itself – always.

To step out of police college is to take the next step into the forest. You are now part of the difference between law and order in the streets where gangs would rule and evil would triumph. But for you and your fellow coppers, society would be a dangerous place. Your mission is to protect society from this evil. Very soon you learn to decide what is evil and what is not. You are no longer just a collector of human rubbish at the base of the cliff but you have an obligation; yes, even a duty to guide the country to a decent society. That direction is best decided by you and others in your sub culture of police, for what better epitomises the values of a decent society than those cherished by the men and women in blue? Your task is honourable. What better vocation than to rid the country of evil? Thus, achieving this end can even justify the means!

The further into the forest, the more pervasive becomes this police culture. The heart of the beast is centered in elite CIB squads like Regional Crime, Criminal Intelligence and Drug Squad. These are the destinations to which the most ambitious and zealous aspire. Together with the Armed Offenders Squad and Team Policing units, these entities are the bastion of police culture.

Of course there are those who do not aspire to these objectives but then, the police is also a government department, which always harbour a good number of “glide timers”: there to collect their pay and do as little as possible, which is the best route to longevity in any government agency. Often these people will suddenly find themselves floating on the top of the pool.

Every new entrant runs the same gauntlet. No recruit is ever formally “taught” to use violence, to lie and cover up. None of my mentors did that to me and I never did it to those whom I mentored. But the culture sends a very clear message. “When you witness transgression by a colleague, keep your mouth shut at worst and at best, provide an account which supports the miscreant and helps him/her out of a sticky situation.”

If you don’t, as a new recruit, you are ostracised. You may as well quit there and then. But once you have provided succor, you have taken your next step into the forest. Later you will witness another indiscretion and you will again “cover”. After all, you have been accepted as one of the team. You are “reliable”. To lose that status is not a desirable outcome. But already you are compromised. Then one day you will commit an indiscretion and others will cover for you. Then you are beholden. Then you have entered the forest proper. There is no light to show the way home.

When I speak about a police culture, I speak about the environment I have described. It is introverted, self protecting and lacking objectivity. It is a culture which looks after itself and has a certain view of how life should proceed. It is reinforced by drinking and bonding sessions. The “them and us” ethos becomes tangible. What is more, the culture is working class conservative in its origins. Bigoted and intolerant. Few of its officer corps are university graduates and even fewer hail from private schools. There is no network which pervades the upper echelons of society. The police are insular.

If someone has tattoos or hair too long or dresses the “wrong” way or does not have “acceptable” politics, then they are one of “them” and not to be trusted. Conversely liberals are a menace to stability and are even more dangerous than unemployed Maori.

I recall when as a detective in the mid seventies, I applied to go to university and was asked by my commissioned officer: ?Meurant. Why do you want to go to university? Are you a communist?? The message was pretty clear. This was at the height of Vietnam. The police subculture did not approve of its members being associated with undesirable elements who frequented establishments of enlightenment.

When I did finally go to university I found my lecturers to include Michael Basset, Phil Goff and Helen Clark, all of whom where later my peers in parliament but who at the time I entered university shared decidedly different political beliefs to me. Yet even though I argued, as an example, that US foreign policy in Vietnam was “defensive” (domino theory), these people approved my assignments. They were prepared to tolerate a philistine within their midst, suppress their natural aversion to me and mark my opinions objectively. This, as I reflect, juxtaposes starkly the attitude or culture of the two institutions. One institution is prepared to tolerate alternative views. The other is not.

I advanced in the rank structure relatively quickly in the police and soon found myself incarcerated as supervisor in a control room; a job I loathed. So I did go to university and here, the first signs of light began to reappear. Slowly the mist began to abate and I saw things from a different perspective. In all, I did eleven years at either Auckland or Victoria universities. I am immensely grateful for how those institutions unwittingly help me exorcise the demon of excessive exposure to police culture.

This “culture” manifests in many different forms. Three recent examples will illustrate my point and demonstrate that it is as alive and well as it was in my day:

John Dewar. Recently incarcerated for, according to the view of the court, covering up for the despicable conduct of assistant commissioner Rickards and two other police officers. John Dewar was one of the best sergeants I ever had as an inspector, but the “culture” manifest in his destiny in a most tragic manner for him.

Then there was the police shooting of a man in Christchurch. The law is clear when a cop or civilian may kill another human being. One must fear, on reasonable grounds, death or grievous injury to oneself or a third person which cannot otherwise be prevented. In my view the circumstances of the killing are not as transparent as the police public relations section would have us believe. A man shot wielding a hammer on cars! Not dissimilar to a man shot wielding a golf club against shop windows.

The proper place to test the validity of police action is before a court. The strength of our police is public confidence and support; without which they are nothing. The best way to retain that public support is for transparency and that is best achieved by testing police actions in a court of law. Yet immediately after the killing we have the police association representative, completely out of line in my view, seeking to influence the outcome by claiming the shooting was justifiable and we should trust the police to judge their own actions. This of course is the manifestation once again of the police culture: look after the police. That is quite different, in my view, to looking after the rule of law.

Finally, there is the recent implementation of draconian anti-terror legislation to combat routine crimes and offences in the community. Police say they have collated information over a period of 12 months which on analysis leads them to the conclusion that there is a real threat to the stability and security of our country. The problem as I see it is, that information they have has been self assessed by the same people who collate the data or, at best, by the supervisor of the “intelligence unit” and his superior; all of whom view society from within the forest and with vested interests in producing an outcome which justifies the retention of their unit. These subjective conclusions are presented to judicial officers as the basis of justification for warrants and implementation of anti terror legislation which abrogate the most basic of our legal rights.

No longer are we protected from arbitrary detention without being charged and the legal requirement to be taken before a court as soon as possible. This I find unacceptable.

I am also disappointed that too many New Zealanders appear not to comprehend the significance of what it means to our legal structure when on the basis of subjective analysis by the police, these guardians substantially usurp the role of the judiciary as a check and balance against tyrannical tendencies. There is a fundamental flaw in the present legislation where it allows a subjective test of police information by police, to form the basis of reason to catapult us onto a terror alert footing. It is even more disturbing to me when I know type of environment where these decision are made, is deep in the forest. What the police are effectively saying is:

“In the Ureweras there are weapons of mass destruction. Trust us.”

Sound familiar?

I have been in the forest. In the seventies I was a detective on the Regional Crime and Drug Squad. I was also on the AOS. My formal police assessments were high. “Excellent” as a detective. “Outstanding” as a commissioned officer. In my formative years my immediate supervisors included detective sergeant John Hughes, detective inspector Graham Perry and later detective inspector Bruce Hutton (Hutton was my boss on my first homicide: the Crewe murders). These men were legends in their own time, each of them relentless and with a determination of mind few could match. Together with half a dozen other young detectives, we formed a formidable unit; we became a legend in our own time.

Our adversaries were serious villains: Peter Fulcher, Mihaly Bede, Terry Clarke alias Mr Asia, the Saffiti boys and several gangs. This was a particularly violent time in the history of policing in New Zealand. We were right in the middle. It was inevitable that we, who consistently faced angry men in dark alleys, would have allegations made against us. I had my share against me.

There were allegations of excessive force; that I was aware of but did nothing about an offender alleged being dangled by his ankles from the fourth floor of the police station; perjury and even one of extracting a confession from a drug dealer by playing on him Russian Roulette with a police issue revolver. These allegations were of course outrageous untruths without foundation and never sustained.

Yeah right!

In 1981 I was seconded to the police Red Escort Group – Red Squad. I later wrote a book about the exploits of the squad. That initiative catapulted me into the headlines for the first time. On the one hand, I believe it provided the impetus for me to gain selection for National as a Member of Parliament in a conservative seat. On other hand, because I later became an MP and had written the book, The Red Squad Story, I became synonymous with Red Squad and alone have endure the odium and contempt heaped upon that police unit, as the tide of public opinion turned.

My last job in the police was inspector in charge of special operations and a criminal intelligence section. At the time the focus was on the activities of Maori activists at Carrington hospital. I took raw police data and used it in my maiden speech. At the time I believed in the conclusions we as a police unit had peer reviewed. Some form of revolution or armed insurrection had been threatened. There were threats of “Kill a white, die a hero”. Maori wanted political sovereignty. Maori activist Sid Jackson was one of several who had been to Libya. But did a contrary political view and aspirations really pose a threat to the security and stability of our country? History has provided the answer. There has been no revolution and at least one of the Maori activists of those times is now in Parliament working within the system.

I made a mistake when I took the raw police data and used in my maiden speech. It took another nine years in parliament, another three years at university and, as I do now, living in Eastern Europe where the legal protections and freedoms we take for granted often do not exist, for me to finally step out of the forest and see it for what it is.

I urge every New Zealander not to allow the state apparatus to take from you by default, legal rights people long before us fought for, died for. I urge every New Zealand to contact their Member of Parliament and express concern that the anti-terror legislation currently before parliament, be placed on “hold” until the true nature of the present police raids under the auspicious of terror legislation, is tested before the courts.

Is a delay of a few months too much to much to ask before we take the next step toward undermining the most significant legal document ever, which has endured since 1215?

The Magna Carta.

Ross Meurant, B.A. M.P.P.

Leave a Reply